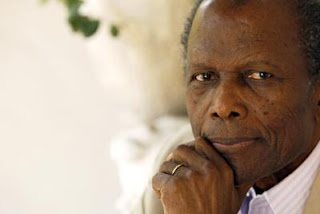

Oscar-winning actress and leading star Sidney Poitier dies AP . news

NEW YORK (Associated Press)--Sidney Poitier, the leading actor and enduring inspiration who changed the way blacks were portrayed on screen, became the first black actor to win the Academy Award for Best Leading Performance and the first box office actor. Sketch, Matt. He was 94 years old.

Poitier, who won the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1964 for "Lilies of the Field," died Thursday at his Los Angeles home, according to Latrai Ramming, communications director for the Prime Minister of the Bahamas. Close friend and great contemporary Harry Belafonte released a statement on Friday recalling their unusual times together.

"For over 80 years, Sydney and I have laughed, cried and done as much mischief as possible," he wrote. “He was really my brother and partner in trying to make this world a little bit better. He definitely made my job a lot better.”

Few movie stars, black or white, have had such an impact on and off screen. Before Poitier, the son of tomato growers in the Bahamas, no black actor would have had a sustainable career as a lead actor or could have had a movie based on his star power. Before Poitiers, few black actors were allowed to break with stereotypes of bug-eyed servants and smiling artists. Before Poitier, Hollywood filmmakers rarely tried to tell the story of a black person.

Messages of honor and mourning for Poitier flooded into social media, with Academy Award winner Morgan Freeman calling him "my inspiration, my guiding light, my friend," and Oprah Winfrey hailing him as a "friend. brother. confidant \ confidant. teacher of wisdom. President cited Former Barack Obama with his achievements and how he revealed "the power of films to bring us together".

The rise of Poitiers reflected profound changes in the country in the 1950s and 1960s. As racial attitudes developed during the civil rights era and apartheid laws were challenged and fell apart, it was Poitier who turned into a cautious industry of progress stories.

He was a fugitive black convict who befriends a white racist prisoner (Tony Curtis) in "The Defiant Ones". He was a court clerk who falls in love with a blind white girl in "A Patch of Blue." He was the handyman of the "Lilies of the Field" who built a church for a group of nuns. In one of the great roles for theater and screen, he was the ambitious young father whose dreams collided with those of other family members in Lauren Hansberry's "A Raisin in the Sun."

Debates about diversity in Hollywood inevitably turn to Poitier's story. His handsome, flawless face. An intense stare and disciplined style, he was for years not only the most popular black movie star, but the only one.

"I made movies when the only other black on the market was a shoe-shine boy," he recalls in a 1988 Newsweek interview. "I was kind of the only guy in town."

Poitier peaked in 1967 with three of the year's most notable films: "To Sir, With Love," in which he starred as a schoolteacher who beats his troubled students at a London high school; “In the Heat of the Night,” said police detective Virgil Tepes; And in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, as the notable doctor who wants to marry a young white woman he's only recently met, her parents played Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in their last movie together.

Theater owners named Poitiers the number one star of 1967, the first time a black actor had topped the list. In 2009, President Barack Obama, whose steadfast influence is sometimes compared to that of Poitier, awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, saying that the actor "not only had fun but was enlightened...revealing the power of the silver screen that brings us closer together."

His appeal brought him burdens not unlike that of other historical figures such as Jackie Robinson and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.. He was subjected to white intolerance and accusations of compromise from the black community. Poitier was held, and held to himself, to much higher standards than his white peers. He refused to play cowards and took on characters, especially in "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner," which is almost divinely good. He developed a steady, yet resolute and at times humorous personality that crystallized into his most famous lines - "They call me Mr. Tepes!" - From "In the heat of the night".

“All those who see my worthlessness when they look at me and are thus given my worthlessness—I tell you, 'I'm not talking about being as good as you. I hereby declare myself better than you,” he wrote in his memoir, “The Man’s Scale,” published in 2000.

But even in his prime, he was criticized for being out of reach. He was called Uncle Tom and "Million Dollar Shoe Shine Boy". In 1967, the New York Times published the essay by black playwright Clifford Mason, "Why does white America love Sidney Poitier so?" Mason dismissed Poitier's films as "a dissociative journey of historical facts" and the actor as a pawn for "the white man's sense of what is wrong with the world".

Stardom did not protect Poitiers from racism and condescension. He had trouble finding lodging in Los Angeles and was followed by the Ku Klux Klan when he visited Mississippi in 1964, shortly after three civil rights workers were murdered there. In interviews, journalists often overlook his work and instead ask him about race and current events.

“I am an artist, man, American, contemporary,” he said during a 1967 press conference. “I have many things, so I hope you will pay me due respect.”

Poitier was not as politically involved as Belafonte, which led to conflicts now and then. But he was active in the March 1963 Washington and other civil rights events, and as an actor he defended himself and risked his career. Refusing to sign an oath of allegiance during the 1950s, when Hollywood was blocking suspected communists, he declined roles he found offensive.

“Nearly all of the job opportunities were reflective of the black stereotyping that afflicted the public consciousness in the country,” he recalls. “I came in unable to do these things. It wasn't in me. I chose to use my work as a reflection of my values.”

Usually Poitier films were about personal victories rather than broad political themes, but Poitier's classic role, from "In the Heat of the Night" to "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner", was that of a black man of such decency and calm—Poitier became A synonym for the word "gracious" - that is, he conquers the whites who are against him.

"Sydney Poitier embodies dignity and grace," Obama wrote on Twitter Friday.

His on-screen career faded in the late 1960s as political movements, black and white, became more radical and films more visible. He did not act as much, gave fewer interviews and began directing, including Richard Pryor's farce Gene Wilder "Stir Crazy", "Buck and the Preacher" (co-stars with Poitier and Belafonte), Bill Cosby's comedy series "Uptown Saturday Night" and " let's do it again. "

In the 1980s and 1990s, he appeared in the feature films "Sneakers", "The Jackal" and several television films, earning him an Emmy and Golden Globe nomination for future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in "Separate But Equal" and an Emmy nomination. For his portrayal of Nelson Mandela in "Mandela and de Klerk". Theater-goers were reminded of the actor by a famous play that featured him in name only: John Guare's "Six Degrees of Separation" about a con artist who claims to be the son of Poitiers.

In recent years, a new generation has learned about him through Oprah Winfrey, who chose "The Guy's Scale" for the book club. Meanwhile, he welcomed the rise of black stars such as Denzel Washington, Will Smith and Danny Glover: "It's like knights coming to relieve the troops! You have no idea how happy I am," he said.

Poitier received several honorary awards, including a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute and a Special Academy Award in 2002, on the same night that the Black artists won two Best Acting Awards, Washington for "Training Day" and Halle Berry for Monster's Ball . "

"I will always chase you, Sydney," said Washington, who earlier presented Poitiers with the honorary award, during his acceptance speech. “I will always follow in your footsteps. There is nothing better to do, sir, nothing better to do.”

Poitier had four daughters by his first wife, Juanita Hardy, and two by his second wife, actress Joanna Shimkus, who starred with him in his 1969 film The Lost Man. Daughter Sidney Tammy Poitier has appeared in TV series such as "Veronica Mars" and "Mr. Knight." The daughter, Gina Poitier-Guregg, passed away in 2018.

"He is our guiding light that has illuminated our lives with infinite love and admiration. His smile was healing, his embrace was the warmest refuge, and his laugh was contagious. We can always turn to him for wisdom and solace and his absence seems like a great hole in our family and our hearts," his family said in a statement. He is no longer here with us in this world, yet his beautiful spirit will continue to guide and inspire us."

His life ended in adulation, but it began in distress. Poitier was born prematurely, weighing just 3 pounds, in Miami, where his parents went to deliver tomatoes from their farm on the tiny Cat Island in the Bahamas. He spent his early years on the remote island, which had a population of 1,500 and had no electricity, leaving school at the age of 12 1/2 to help support the family. Three years later, he was sent to live with his brother in Miami; His father was concerned that street life in Nassau was having a bad influence. With $3 in his pocket, Sydney traveled on a postal cargo ship.

“The smell in that part of the boat was so horrible that I spent a good part of the crossing going up from the side,” he told The Associated Press in 1999, adding that Miami soon taught him about the racism. "I quickly learned that there were places I couldn't go, and that I would be questioned if I walked around different neighborhoods."

Poitier moved to Harlem and was so overwhelmed with his first winter there that he joined the army, cheated on his age and swore he was 18 when he had just turned 17. Doctors and nurses cruelly treated sick soldiers. In his 1980 autobiography, This Life, he recounted how he escaped from the army by pretending to be insane.

Back in Haarlem, he was searching in Amsterdam news for a job as a dishwasher when he noticed an ad looking for actors at the American Negro Theatre. He went there and was handed a text and asked to go up on stage. Poitier had never seen a play in his life and could hardly read. He stumbled into his lines with a thick Caribbean accent and the director led him to the door.

“As I walked to the bus, what insulted me was the suggestion that all he could see in me was a dishwasher. If I succumbed to it, I would help him make that perception a prophetic one,” Poitier later told the AP.

“I was very upset, and I said, 'I'm going to become an actor — whatever that is. I don't want to be an actor, but I have to become an actor to go back out there and show him that I can be more than just a dishwasher. "This became my goal."

The process took months as he uttered the words from the newspaper. Poitier returned to the American Negro Theater and was rejected again. Then he made a deal: he worked as a theater janitor in exchange for acting lessons. When he was released again, fellow students urged the teachers to let him participate in the class play. Another Caribbean region, Belafonte, was in the lead. When Belafonte was unable to give a preview performance because it conflicted with his guard duties, he pursued his colleague, Poitier.

Among the audience was a Broadway producer who portrayed him in an all-black version of "Lysstrata". The play lasted four nights, but Poitier's enthusiastic comments earned him an alternate job on "Anna Lucasta," and he later starred in The Road Company. In 1950, he appeared on screen in No Way Out, playing a dying doctor whose patient, a white man, is then harassed by the patient's fanatical brother, played by Richard Widmark.

Major early films included "Blackboard Jungle," which featured Poitier as a difficult high school student (the actor was in his twenties at the time) at a violent school. and "The Defiant Ones," which landed Poitier his first Best Actor award, and his first nomination for any black man. The theme of cultural differences becomes a hilarious theme in "Lilies of the Field," where Poitier plays a Baptist handyman who is building a church for a group of Roman Catholic nuns, who are refugees from Germany. In one of the most memorable scenes, he gave them an English lesson.

The only black actress before Poitier to win a competitive Oscar was Hattie McDaniel, Best Supporting Actress for 1939 for "Gone With the Wind." No one, including Poitier, thought "Lilies of the Field" was his best film, but the times were right (Congress was soon to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which Poitier lobbied for) and the actor was favored even against such competitors as Paul Newman, "Hud" and Albert Finney, "Tom Jones." Neumann was among those in favor of Poitiers.

When presenter Anne Bancroft declared his victory, the audience rejoiced for so long that Poitier momentarily forgot his speech. "It's been a long journey up to this point," he declared.

Poitier never pretended that his Oscar was a "magic wand" for black performers, he noted after his win, and shared his critics' frustrations with some of the roles he took, acknowledging that his characters were sometimes so asexual that they became kind. From "neutral". But he also believed he was lucky and encouraged those who followed him.

“To the African American filmmakers who have come onto the playing field, I feel proud that you are here. I am sure, like me, that you discovered that it was never impossible, it was even more difficult,” he said in 1992 when he received a Lifetime Achievement Award From the American Film Institute. "

“Welcome, young blacks. Those of us who go before look back in relief and leave you with a simple confidence: Be true to yourselves and be useful on the journey.”

Associated Press writer Robert Gillis in Toronto, AP film writer Jake Coyle, and former Associated Press writer Polly Anderson in New York contributed to this report.

Yorumlar

Yorum Gönder